Louis Ribak

LOUIS RIBAK (1903-1979), moved to Taos in 1944.

In his first show in eight years [Louis Ribak] reports from Mexico and the Southwest with added strength and color. There is new freedom with emphasis on forms as such rather than on objects ...

—New York Times, May 1954

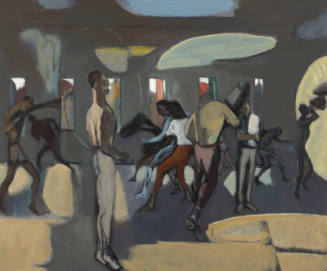

Beginning with work that was included in the 1934 Venice Biennale and continuing with his social realist painting of the 1930s, Louis Ribak captured vibrant images of urban life with considerable power. He was making an important career when, in 1944, he abandoned New York for Taos with his wife, Beatrice Mandelman. Various reasons have been suggested for the move: Ribak’s health; John Sloan's suggestion that the couple move to New Mexico; and their general disenchantment with New York. All these were probably contributing factors, but, since there was a good deal of wanderlust in Ribak, perhaps he just needed a change. As curator Harry Rand observed in the catalog of a 1984 exhibition of Ribak’s late paintings,

Something entirely unsuspected gripped Ribak in the Southwest and he was never able to disenthrall himself from the heady solemnity of the landscape, its beauty or emotive potential.

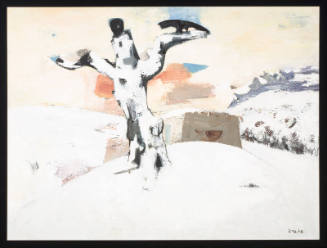

Ribak's approach shifted from social realism to full abstraction during his Taos years. Much of his early Taos work consists of semi-abstract landscapes, artistically descended from the paintings of American artist Albert P. Ryder. In Ryders’ work there is a living aspect to the environment in which humankind is not isolated, but is instead an intimate part. Ribak seems to have brought this concept with him from New York but, under the powerful influence of contact with New Mexico's pueblos, it was dramatically reinforced, expanded, and adapted to the changed circumstances of his life. He had to change to meet the demands of the new environment. Mandelman later said, “We had to start all over again. We spent the first couple of years painting the landscape” as a means of coming to understand the West.

Highly respected by his peers, Ribak was looked up to by the Taos Moderns as “an elder compadre,” a role model. In 1947, he opened the Taos Valley Art School for returning veterans who used their GI Bill benefits to pay tuition and living expenses. In addition to attracting beginners, mature artists who needed no training used the stipend to enable them to continue painting and drawing. Ribak, like Andrew Dasburg, offered no ideology to his students: “I’m not truly anything. I’m against everything. Damned abstract[ionist]s, realists, illustrators …” He condemned taking any single approach—he believed this would lead to academicism, an art of deadness, whether abstract or representational.

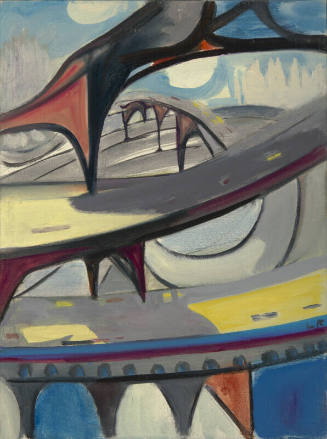

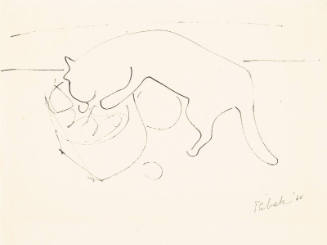

Ribak was well-acquainted with the work of the abstract expressionists and knew artists of the New York School. In the mid-1950s, Mandelman and Ribak sojourned in New York, then returned to Taos. From that time, Ribak developed the lyrical abstract expressionism that would occupy much of his subsequent career. Movement No. 1 and Movement No. 2 are examples. The flowing calligraphy evident in much of his work developed from decades of landscape drawings. His abstract paintings seem not to have come from cubism so much as out of his own preoccupation with working directly from nature.

Edited excerpt from David L. Witt, Taos Moderns: Art of the New (1992).