Thomas Benrimo

THOMAS BENRIMO (1887-1958), moved to Taos in 1939.

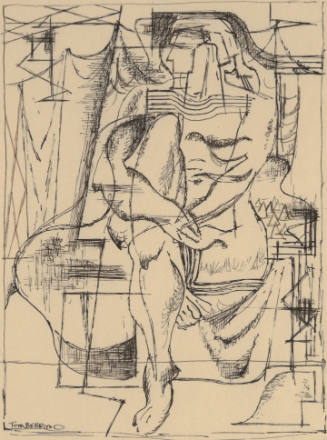

The flowing quality of design which Tom Benrimo subtly employs suggests a penetrating musical quality.

—Allen S. Weller, 1952

In an art community known for its reclusive artists, Thomas Benrimo stood out by his absence from the art scene in his early Taos years. He lived in Taos for over twelve years before sharing his work with the public for the first time in a group exhibition at the Hotel La Fonda in 1951.

Benrimo moved to Taos in 1939 on the strength of winning the Art Director Medal for Color Illustration award, an honor that included a $5,000 prize. He left New York’s Pratt Institute, where he had taught such courses as “Applied Surrealism” for commercial artists. A painter whose roots went back to the early days of American modernism, he now had the means to make the transition back into fine art, which he had abandoned in order to support his tubercular mother and brother.

His first artistic project in Taos, done in partnership with his wife, Dorothy Benrimo, a fine jeweler, was converting an old adobe ruin into a stately home. In his early Taos paintings, he attempted to regain the position that he had staked out more than 20 years earlier in New York. Little of his work from that period remains, but it is clear that the 1913 Armory Show deeply impressed him; he painted abstractions by 1918, if not before.

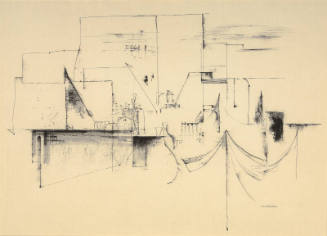

His Taos work included subject matter suggested by ancient Roman and Etruscan art and Greek vase painting, and also influenced by cubism. His facility for painting detail exceeded that of most artists, and his studies of modernist painting during his teaching career made him one of the best informed artists in the country. His teaching notes reveal a brilliant mind which welded together the many currents of modernism to make them understandable to his students. Benrimo's reputation was such that László Moholy-Nagy, an artist and founder of the New Bauhaus art school in Chicago, invited him to become the school’s director in the 1940s. But, by that time Benrimo had decided to devote the remainder of his life to painting.

During the war years, he concentrated on finely crafted surrealistic paintings. In the 1950s, Benrimo combined surrealism and strong structural form with lyrically tragic and passionate themes, as seen in late work such as White Moon #2 (ca. 1954).

Benrimo's work achieved national exposure when one of his paintings was included in the 1951 “Contemporary American Painting and Sculpture” exhibition at the University of Illinois. Asked to comment on his work for the catalog, he said (quoting author Charles Norman): “Feeling and form are all; and that man is most an artist who fuses those two into an indivisible one.”

Edited excerpt from David L. Witt, Taos Moderns: Art of the New (1992)

![Untitled [abstracted drawing]](/internal/media/dispatcher/2892/thumbnail)

![Untitled [drawing of three rocks]](/internal/media/dispatcher/4200/thumbnail)