Janet Lippincott

1918-2007

Returning to New York she attended the Todhunter School, a private school for upper-class girls offering courses in the arts and a college preparatory program. Associate Principal Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, taught American history, American literature, English and current events to juniors and seniors before the school merged with the Dalton School in 1939. When she was fifteen, Lipincottt’s mother enrolled her in a life drawing class as the Arts Students League in New York, but she was taken aback when a male nude entered the room and she promptly left the class. She later returned after a female nude became the art model. After graduating high school she returned to the League full time.

During World War II she enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) and worked for a time in General Dwight Eisenhower’s European office dealing with the press corps and determining who was allowed to see him. She later enjoyed relating how she told General George Patton to take a seat and keep his mouth shut after he stormed into Ike’s office demanding to see him. While stationed in London during the Blitz – the Nazi Luftwaffe’s strategic bombing of British cities – she suffered a broken back after falling several floors through a bombed out building during the attack. The injury caused her debilitating pain later in life.

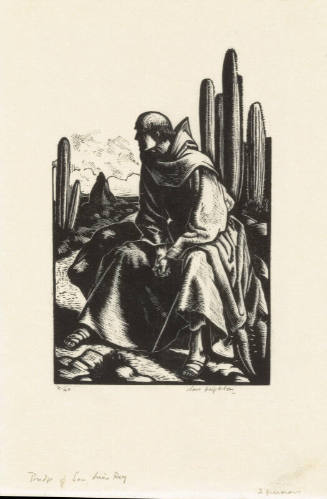

After returning to the United States from Europe in 1945, she decided to go to secretarial school on the G.I Bill that provided a range of benefits for World War II veterans including payment of tuition and living expenses to attend college or vocational/technical schools. “I was lousy,” she later recalled. Knowing that she could draw and paint, she made her first road trip west of the Hudson River in the summer of 1949 to study on the GI Bill at the Taos School of Art with Emil Bisttram, co-founder with Raymond Jonson of the Transcendental Painting Group. However, Bisttram did not appreciate her talent and told her that she was wasting her time. Twenty-three years later he recognized her accomplishments with a glowing review of her exhibition at the Jamison Gallery in Santa Fe.

Undaunted by her former teacher’s criticism, in the early 1950s she received fellowships to study at the California School of Fine Arts (now the San Francisco Institute of Art) and at the Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center with Emerson Woelffer and Mary Chenoweth. Her teachers at both institutions provided her with an excellent introduction to Abstract Expressionism that distinguishes much of her creative output, although she also did referential abstraction and figurative work. The only realistic work she did from the 1960s on were figure drawings, generally as a member of the John Sloan Drawing Group conducted by Bob Ewing, former director of the New Mexico Museum of Art in Santa Fe. She “loved the aesthetic and quality of drawing, the feeling of that emotion, the freedom of drawing.”

In 1954 she settled in Tesuque, New Mexico, relocating in 1956 to Santa Fe where she built an adobe home and studio on Canyon Road. In an interview for the Albuquerque Journal in the last years of her life she recalled, “After the war I came out here and no one was doing any modern painting. Here I came with my screwball ideas and I shook everybody up.” Although it took time for her to be accepted by critics in Santa Fe, she enjoyed a remarkable career from the 1950s to the 1970s with a number of prestigious awards, solo and group shows to her credit.

Her oil painting, Song of Autumn (1957 or 1959), exemplifies her impasto, rhythmic Abstract Expressionist style of the 1950s and 1960s. Its strong composition and palette, gesture and line help to convey the emotive qualities and feeling attached to the Fall season with its brilliant display of color before being supplanted with the onset of winter. In a Southwest Art article in 1980 she described her approach to abstract painting and its importance for her: “Abstract painting is an intellectual process. To be a modern painter and to make a truthful statement is the sum total of all I am and what I am continually striving to create. I am a painter and my feelings are all I can contribute to this world.”

She was briefly married for ten days to artist John Skolle with whom she had briefly studied in New Mexico, but it was “10 days too long,” as she later told Karen Ruhlen, her art dealer in Santa Fe. While she enjoyed male company, Ruhlen recalled that she was “an artist to the core. Making art was like breathing – it was her way of expressing her emotions.” She never pre-planned any of her paintings, but “worked spontaneously and in the moment.”

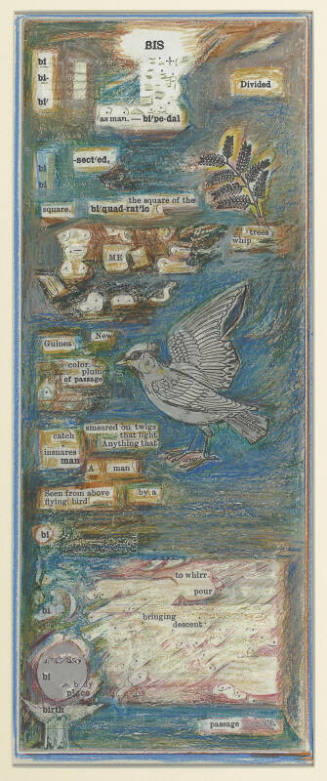

In addition to her paintings, for which she primarily is known, she was a guest artist at the Tamarind Institute after it was created in 1970 as a division of the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. Originally founded a decade earlier as the Tamarind Lithography workshop in Los Angeles, it functioned as an American print shop serving artists when many of them tended to reject lithography and collaborative printing in favor of the more “direct…immediate” possibilities of abstract expressionist painting.” At Tamarind she produced a series of lithographs, although she previously worked in the medium in the 1950s.

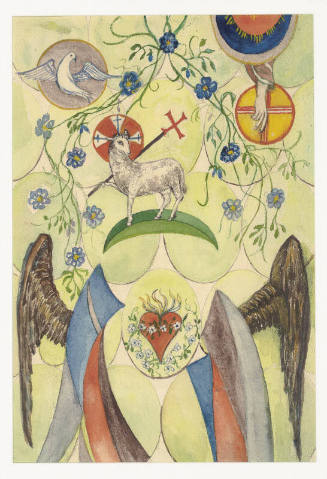

She began bronze sculptures soon after the Shidoni Foundry opened in 1971 as part of an art community in nearby Tesuque, New Mexico. They depict in a three-dimensional format the abstract expressionist forms employed in her two-dimensional work. Some of her sculptures have titles taken from Biblical psalms, such as They That Go Down to the Sea in Ships, from Psalm 107:23. Her sculpture, The Man Who Would Be King, is based on the title of Rudyard Kipling’s story about two British adventurers in British India who became kings of Kafiristan, a remote part of Afganistan. Another, more somber source of inspiration seen her work on paper was the legacy of World War II and the Vietnam War. Her European wartime experience made her an outspoken critic of war throughout her life.

In the late 1970s and into the 1980s she began experimenting with acrylics. During the 1980s she became interested in monoprints which she created at the College of Saint John in Santa Fe and participated in the school’s Monothons. In the 1980s increasing health issues stemming from her wartime injury forced her to exchange her large, colorful oil paintings and three-dimensional collage pieces for small watercolors that physically proved more manageable.

Lippincott remained an important modernist and a key component of Santa Fe’s abstract artists’ community. In her later years, however, she suffered from a lack of recognition because she was more committed to her work and somewhat less interested in promoting it. Relishing her independence from the New York School of painting, she derived inspiration from the intense color and form of her New Mexico environment that imparted mystery and impact to her work.

In the last decade of her life into the 21st century she received new attention in the context of the developing interest in abstraction in the West. Her work has been included in two exhibitions of New Mexico modernists: “The Second Wave: New Mexico Modernists after World War II,” at the Karen Ruhlen Gallery in Santa Fe in 2007, and “New Landscapes, New Vistas: Women Artists of New Mexico,” at the Matthews Gallery, also in Santa Fe, in 2016.

Her lengthy career was capped with the 2002 New Mexico Governor’s Award for Excellence in the Arts and the 2003 Arts Achievement Award from the New Mexico Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC.

The Santa Fean magazine wrote upon her death in 2007: “Compositionally akin to Matisse and Picasso, but with softer contrasts, kinder hues and an innately more fluid if gauzy way with lines and shapes, Lippincott ended up an artist’s artist, and created lasting images of the female form and abstract arrangements of emotionally rich and inviting shapes.”

On the occasion of her 70-year posthumous retrospective exhibition at the Matthews Gallery in Santa Fe in 2016, it was noted: “Whatever obstacles she faced, she never wavered from her strong and committed artistic vision. The best of her work stands equally alongside the noted artists of the period.”

http://www.modernistwest.com/jimmy-ernst-1

Person TypeIndividual

United States, 1923 - 2018