Hispanic Traditions

The Harwood Museum is fortunate to have an important collection of Hispanic works that covers a broad range of the historic traditions of northern New Mexico. Paintings as well as objects in tin and wood show that significant art based on European traditions was being created in the Taos area long before the Taos Art Colony began in the late 19th and early 20th Century.

The New Mexico carpiñteros have a long history going back to the beginning of Spanish colonization. Given the high cost of importing furniture from Mexico City, New Mexicans established numerous carpentry shops of their own. Local craftsmen using simple tools created basic furniture items. Examples of late 18th Century/early 19th Century pieces cajas (storage chests), harineros (grain chests), and trasteros (kitchen cupboards) are included in the Museum collection. Burt and Elizabeth Harwood collected some original works around 1916 and had others restored. The largest grain chest in the collection (shown below) was made at the Valdez workshop in Taos County and includes incised asterisk markings which seem to have been characteristic of that shop. Other chests still retain traces of blue and red pigment showing that in their original state they were brightly painted.

The later developing tradition of New Mexico tin work served as an integral part of Hispanic religious culture during the 19th Century. It began with the importation of Mexican tin work and the opening of the Santa Fe Trail which provided local artisans with the materials. When railroads connected New Mexico with the eastern United States in the 1880s, tin work reached its artistic height. Tin cans, glass panes and religious prints were fashioned into devotional objects used in domestic and ecclesiastic settings. Between 1840 and 1915 thirteen workshops in New Mexico produced unique designs based on specific decorative techniques. The inventiveness of the tinsmiths is evident in their creative use of the available tools and materials.By the turn of the century most tinsmiths stopped making religious objects, focusing instead on secular items such as sconces, lanterns and trinket boxes.

Not only furniture and tin work, but also architecture and colcha embroidery found a new popularity in the Southwest during the 1920s-1930s Spanish Colonial revival. Several projects funded either by the State and Federal governments or private foundations hired instructors to teach crafts to a new generation. One important project was the major expansion of the Harwood. Revival pieces in wood and tin were produced in vocational programs such as the New Deal's Taos Crafts smithing and furniture school. During 1937-38 Max Luna, Director of the program, and his students produced exemplary tin work chandeliers for the Harwood. They also created armarios (cabinets), bancos (benches) as well as mesas (tables) and sillas (chairs). Sixty years after their creation, they are still in use in the offices and galleries of the Harwood.

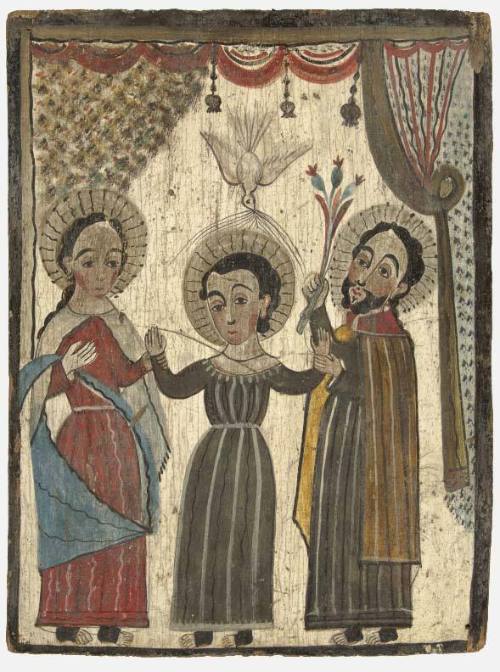

Another of the well recognized art forms of Hispanic New Mexico are Santos, sacred images of Roman Catholicism. Early pieces from New Mexico date from the late 1700s. Most of the Santos in the Harwood collection were a gift from Mabel Dodge Luhan and date from the classic period of 1800-1850, although there are late 19th Century and contemporary works as well. The artists (Santeros) were commissioned to create these sacred images by churches, families, and devout individuals. Today the tradition of the Santero continues in New Mexico using historic styles and techniques.

One of the most important artists to influence today's santeros was Patrociño Barela (1900-1964). The Harwood houses the largest publicly owned collection of wood carvings by this artist. Acclaimed as "discovery of the year" by Time magazine in 1936, Barela's carvings received their national premier at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in a show featuring artists of the Federal Art Project. Several pieces from that show are owned by the Harwood. Although some of his work is on religious themes, he rejected the label of Santero since he did not create specifically for religious purposes. The majority of his output was secular in nature. He examined all aspects of the human condition with an emphasis on relationships within the family. Stylistically his sculpture has affinities to both 11th Century Romanesque and to 20th Century expressionism. Barela's success in creating such a large and complex body of work is unusual for a person of such humble origins. He was the first Mexican-American artist to attain national attention. Barela is considered a visionary artist, since he developed a modern style all his own.